How I Optimized My Way to a Free MacBook Battery Replacement

How I used IOKit and the SMC to get a free battery replacement before my AppleCare expired

After upgrading to an M4 MacBook Pro 16-inch, I wanted to sell my old M1 MacBook Pro 16-inch to offset some of the cost. Before listing it I did the usual checks: cosmetics, storage, battery. The battery health was at 82%. Not terrible, but buyers notice that kind of thing. Then I remembered I still had AppleCare Plus on it and looked up the replacement policy. Apple will swap your battery for free if the maximum capacity drops to 79% or below before your plan expires. Selling a MacBook with a fresh battery is a completely different proposition than selling one at 82%. My AppleCare had a few weeks left. I needed 3%.

Here’s how I killed the battery on purpose and got Apple to replace it for free. The tool is open source on GitHub.

How Macs control charging

The first question was whether it’s even possible to programmatically control charging on a Mac. I went down a rabbit hole trying to find out how macOS manages power at the hardware level, and kept running into the same name: the System Management Controller, or SMC. It handles thermals, fan speed, sleep/wake, LED indicators, and most importantly for my purposes, battery charging.

The problem is that Apple doesn’t document any of this publicly. There’s no developer guide, no API reference, nothing. A developer asked Apple directly on the developer forums and got silence. The Apple Wiki has a decent overview of what the SMC is, and Howard Oakley’s writeup goes deeper into how it fits into the boot and power management stack. But the real breakthrough was a GitHub issue on the bclm project where people had reverse-engineered the specific SMC keys that control charging. That’s where I learned about CH0B, CH0C, CH0I, and CH0K. Writing 02 to CH0B and CH0C tells the SMC to block charging. Writing 01 to CH0I forces the Mac to discharge even while plugged in. Writing 00 to all of them restores normal behavior.

Here’s a sample of the SMC key interface. A given Mac can have hundreds of keys covering thermals, fans, voltage, current, and more - these are just the ones relevant to battery and charging:

One important caveat: this approach only works on Apple Silicon Macs (M1 and later). The CH0B/CH0C/CH0I keys were reverse-engineered on M1 machines and worked across M-series generations, but Apple’s macOS 15.7+ firmware replaced them with a new set of keys: CHTE for charging control and CHIE for forced discharge. Nothing to worry about though, this tool detects which keys your machine supports at startup by attempting to read each one, if the key doesn’t exist, the call returns a non-zero error code and the tool falls back to the legacy set.

The math

Apple defines battery health as the ratio of current max capacity to the original design capacity:

Fun fact: this formula doesn’t match what Apple shows you in System Settings (this confused the heck out of me). My M4 MacBook Pro reports AppleRawMaxCapacity of 8342 mAh and DesignCapacity of 8579 mAh, which gives 97.24%. But System Report says “Maximum Capacity: 99%.” Trying AppleRawMaxCapacity / NominalChargeCapacity (8342 / 8586) gives 97.16%, also not 99%. None of the simple ratios between exposed IOKit keys reproduce Apple’s number. There’s almost certainly calibration data or a cell aging model involved that isn’t exposed. Either way, AppleRawMaxCapacity / DesignCapacity is the right formula here because it measures actual physical capacity, and that’s what Apple’s 80% warranty threshold is based on.

Anyways, so my good old M1 MacBook Pro 16-inch reported a DesignCapacity of 8694 mAh, therefore I needed my max capacity to drop below 6868 mAh to hit that 79% threshold. The plan was simple: automate full charge-discharge cycles until the health drops enough. Apple’s design spec says MacBook batteries retain 80% of original capacity at 1,000 charge cycles, which averages out to about 0.02% degradation per cycle. My battery was already at about 700 cycles when I started, so in theory it had already used up most of its “easy” degradation. But that 0.02% figure is for normal use with shallow discharges. Battery University’s research on lithium-polymer cells shows that full depth-of-discharge cycles wear the battery about 6-7x faster than shallow ones. So I was expecting something closer to 0.04-0.08% per cycle. From 81.8% down to 79% is a 2.8% drop, which meant somewhere around 35-70 full loops.

Building the tool

Here’s how deep the stack goes from a Python script down to the actual hardware:

There are a few distinct capabilities the tool needs. Here’s what each one requires and how to get it:

- Detect if a charger is connected -

IOKit/IOKitLib.hto query theAppleSmartBatteryIOService forExternalConnected - Read battery percentage - same IOService, key

AppleRawCurrentCapacity - Read battery health - same IOService, keys

AppleRawMaxCapacityandDesignCapacity - Disable/enable charging - smcFanControl’s smc.c, write to SMC keys

CH0B/CH0C(legacy) orCHTE(macOS 15.7+) - Force discharge while plugged in - same smc.c, write to SMC key

CH0I(legacy) orCHIE/CH0J(macOS 15.7+)

The battery reads all come from one IORegistryEntryCreateCFProperties call, which dumps the entire AppleSmartBattery dictionary in one shot. For the SMC side, the smcFanControl project has a solid C implementation for reading and writing SMC keys, but it’s structured as its own CLI tool with main() and argument parsing. I needed just the raw read/write calls, so I wrote a thin wrapper around the low-level functions. Each call opens and closes its own SMC connection so the Python side never has to manage IOKit handles. For the battery data, I wrote my own C against IOKitLib.h.

Here’s roughly what the battery reading code looks like:

#include <CoreFoundation/CoreFoundation.h>

#include <IOKit/IOKitLib.h>

typedef int MilliampHours;

typedef struct {

MilliampHours current_capacity;

MilliampHours max_capacity;

MilliampHours design_capacity;

int cycle_count;

bool is_charging;

bool is_plugged_in;

} BatteryInfo;

BatteryInfo FetchBatteryInfo(void) {

BatteryInfo info = {0};

io_service_t entry = IOServiceGetMatchingService(

kIOMainPortDefault, IOServiceMatching(kAppleSmartBattery));

if (entry == IO_OBJECT_NULL) {

return info;

}

CFMutableDictionaryRef properties;

kern_return_t result = IORegistryEntryCreateCFProperties(

entry, &properties, kCFAllocatorDefault, 0);

IOObjectRelease(entry);

if (result != kIOReturnSuccess) {

return info;

}

GetDictInt(properties, kCurrentCapacityKey, &info.current_capacity,

kCFNumberIntType);

GetDictInt(properties, kMaxCapacityKey, &info.max_capacity, kCFNumberIntType);

GetDictInt(properties, kDesignCapacityKey, &info.design_capacity,

kCFNumberIntType);

GetDictInt(properties, kCycleCountKey, &info.cycle_count, kCFNumberIntType);

GetDictBool(properties, kIsChargingKey, &info.is_charging);

GetDictBool(properties, kExternalConnectedKey, &info.is_plugged_in);

CFRelease(properties);

return info;

}Calling C from Python

With the C side figured out, I needed to wrap these IOKit and SMC calls so I could use them from Python. Python is just a nice front end for C libraries anyway - half the standard library is C under the hood, and writing a CLI with argument parsing, logging, and a sleep loop is a lot more pleasant in Python than in C, even though I as using the ultra modern C23. There are three main options for bridging the two languages, and they each make different trade-offs:

| Feature | Python C API | CFFI | Cython |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syntax | C with PyObject1 | C declarations as strings in Python | Cython syntax (.pyx files) |

| Verbosity | Very verbose | Minimal | Medium |

| Learning Curve | Steep | Low | Medium |

| Build Dependencies | None (built-in) | cffi package | cython package |

| Runtime Dependencies | None | cffi package | None |

| Compiled Wheels | Yes (.so/.pyd) | Yes | Yes |

| Boilerplate | High (PyMethodDef, ref counting) | Low (declare and call) | Medium (.pyx wrappers) |

| Performance | Fastest | Fast | Fast |

I really wanted an excuse to use Cython because it sounds like a Pokémon evolution of Python, but CFFI was the right call. For a small project like this where I’m wrapping a handful of IOKit and SMC calls, the minimal boilerplate wins out. You declare the C functions as strings (yes this is gross) and CFFI handles the rest. The trade-off is no syntax highlighting or IDE support for those declarations, and a runtime dependency on the CFFI package. I wrote a .pyi stub file so the Python side still gets type hints for the C functions. First time I’ve ever had a legitimate reason to create one of those. Both the smc.c code and my custom IOKit battery code get compiled together and shipped as a precompiled Python wheel, so end users don’t need a C compiler or any system headers installed.

Putting it all together

With the IOKit bindings and SMC control wrapped in Python via CFFI, the tool automates charge cycling to degrade the battery down to the 79% threshold. Here’s how the logic works:

The key idea is that the Mac stays plugged in the entire time. The SMC keys let the tool force the battery to discharge even while connected to power, and then re-enable charging when it’s time to fill back up. That means I could just start it, walk away, and let it loop unattended for days. No unplugging, no babysitting. It drains to 5%, charges back to 95%, checks health, and repeats. The program stops itself once it hits the 79% target, re-enabling normal charging on exit.

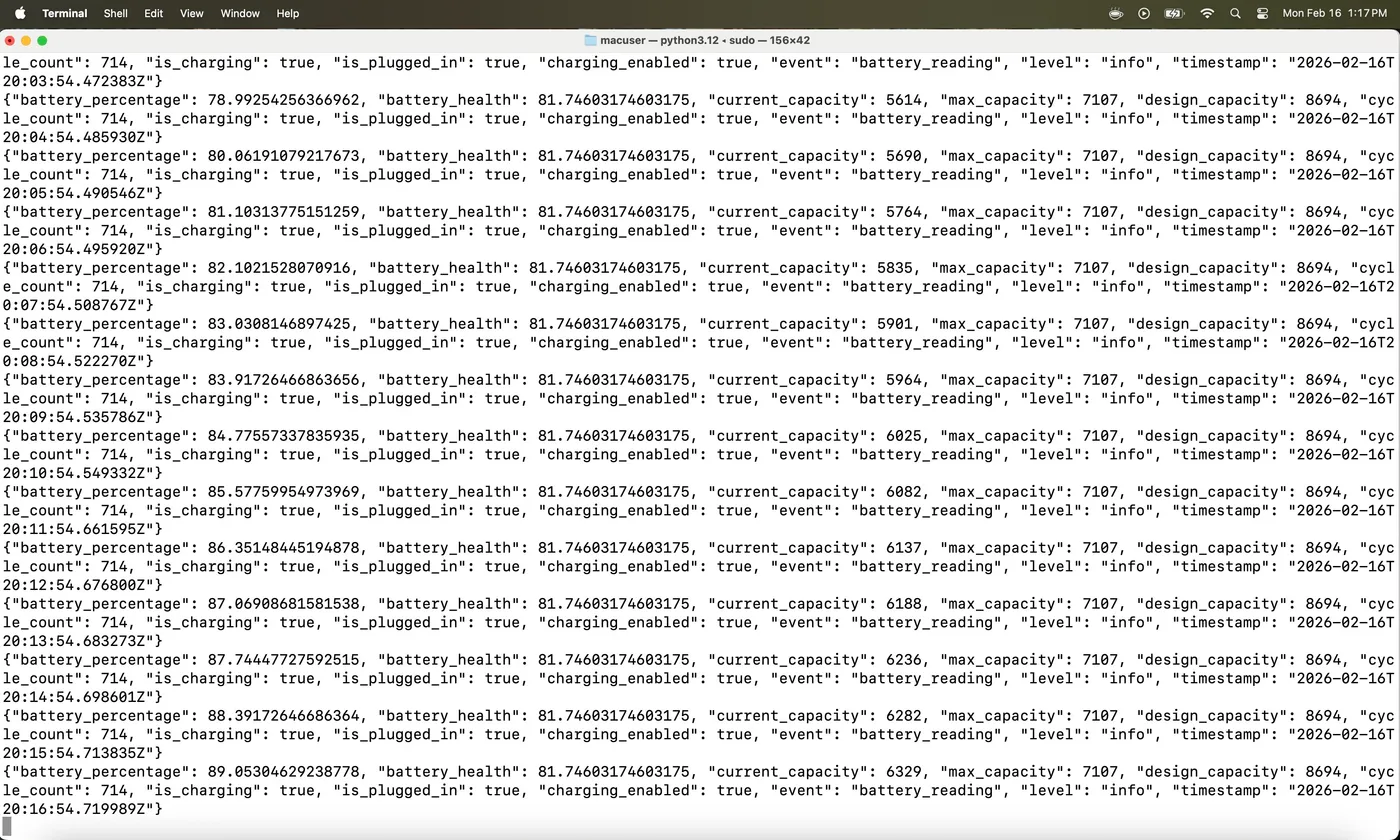

Since I’d already migrated to the M4, I factory reset the M1, installed uv, and ran sudo uvx battery-tool. That’s it. Here’s what it looks like in the terminal (yes, that’s the default macOS Terminal.app on a fresh install), each line is a structured log entry2 with the current battery percentage, health, capacity, and cycle count. The full logs are in this gist if you want to see every cycle.

battery-tool running cycles on a fresh macOS install

One thing to do before running this: turn off Optimized Battery Charging in System Settings > Battery. macOS learns your charging habits and will cap the charge at 80% if it thinks you’re going to stay plugged in. That directly fights what we’re trying to do here, since the tool needs to charge all the way up to 95% to get a full depth-of-discharge cycle. Unfortunately there’s no way to disable this programmatically, but it’s only a one-time manual step. I also used the open source Caffeine app to keep the Mac from going to sleep during the cycling process, since a sleeping Mac will pause the discharge.

Results

I work with data, so naturally I had to track the degradation and put together a chart. To speed up each discharge cycle, I ran HDR YouTube videos on loop at full brightness - the display and GPU chew through battery much faster than an idle desktop. Starting at cycle 700 with 81.8% health, the tool ran for about 95 cycles over roughly two weeks. Each cycle took 4-5 hours depending on what else was running. Here’s how the health tracked over time:

The degradation wasn’t perfectly linear. Early cycles chipped away at about 0.02% each, but as the battery wore down the rate picked up closer to 0.04% per cycle, consistent with what Battery University’s research predicts for deep discharge cycling. The tool stopped itself at cycle 795 when health hit 78.88%, safely below the 79% threshold. I booked a Genius Bar appointment, they ran diagnostics, confirmed the battery was below spec, and swapped it on the spot under AppleCare. Total cost: zero dollars and about two weeks of patience.

1 PyObject is the base C struct that represents every Python object at the C level. “Everything in Python is an object” sounds philosophical until you’re manually incrementing reference counts on one.

2 The logs come from a library I’m a fan of called structlog, which outputs key-value pairs instead of free-form strings. Every log line is machine-parseable out of the box, so one could pipe the output through jq to easily filter for specific data. Standard library logging can technically do structured output, but structlog makes it the default instead of something you have to fight for.